Who Is Sunbonnet Sue?

A female who inspires great passion is inherently interesting. Often she is someone people either love or hate – there is no in between. In the quilt world that person would be someone everybody knows but with a past you can’t quite pin down – Sunbonnet Sue.

Her origins are murky; her appliquéd self seems to appear full-blown in the sources that can be listed for Sue. Is it possible that long traditions of non-textile artistic expression helped build her up to the quilted creation we now recognize?

Featured: Sunbonnet Sue Bed Runner Pattern

Consider...

Early in human history someone thought it was a good idea to paint one-dimensional silhouettes of animals inside caves and carve them on rocks. A while later, the Egyptians showed us how they walked in stylized images accompanying their hieroglyphics. In our own not-so-distant past, coloring books have provided outline drawings of everything you can think of.

And oh yes – paper dolls for many quilters were the first opportunity to play with color and flat human figures. In use for hundreds of years, paper figurines appeared regularly in the mid-18th century in Europe.

In 1800, McLoughlin Brothers began producing paper dolls in America. After Milton Bradley Company, known for its games division, bought them out in 1920, the popularity of paper dolls soared. That flat aspect, those interchangeable clothes via fabric choices, this inexpensive source of inspiration – there must have been significant cultural media overlap to bring Sunbonnet Sue to life on so many quilts.

Not to mention that appliqué has a long-standing place in universal human artistic endeavors, including ceramics, collage -- even military armor plating -- as well as cloth manipulation.

So, Sue’s “mysterious” profile isn’t all that much of a stretch from how humans have been depicting things for a very long time. And as with everything under the sun, nothing is new; borrowing happens; copying is common; and lots of smart, creative people can come up with the same idea at more or less the same time.

Accepting that Sunbonnet Sue’s uncertain origin doesn’t matter all that much, we turn to what we do know about this beloved/despised textile appliqué character.

Sunbonnet Sue, Documented

First, set aside the notion that any quilt block or pattern or appliqué can only be known by that one name. Although this can be true, it often is not accurate. As ideas were copied (some better than others) and shared and reproduced by thousands of individuals, changes were bound to happen. Regionalism in speech and plain old mistakes in understanding gave and continue to give rise to variations in spelling and nomenclature.

Featured: GO! Sunbonnet Sue Block Pattern

The rise of literacy among women in the mid-to-late 19th century and the proliferation of written and published quilt patterns in the early 20th century did much to standardize and replicate creative ideas. Books dedicated to just quilting were slow to come along until the 1970s and 80s, but among the few predating the “Golden Era of quilt book publishing” was 1900’s “The Sun-bonnet Babies” by Bertha Corbett Melcher of Minneapolis, Minnesota. (The book was published under “Bertha L. Corbett;” the hyphen was dropped after this first of two self-published books on the bonneted figures).

Sue appeared on the heels of the very popular Kate Greenaway figures and Palmer Cox’s Brownies, both of whose artworks show up on early 20th century quilts in embroidery and applique, so the trend was there; Bertha had great timing. Collaboration on nine additional Sunbonnet books with Eulalie Grover Osgood cemented Bertha’s position as the Mother of Sunbonnet Sue.

Not far removed in time from the great westward migration across America and still very much tied to an agrarian lifestyle, even as the Industrial Revolution boomed and grew great cities, the notion of sunbonnets protecting faces and shielding eyes in a life lived mostly outdoors must have been a strong nostalgic pull for women who still made most of their families’ clothing and household items by hand. (Or by machine. Women are smart and as soon as a nifty tool for making their endless chores easier came along they adopted it as soon as they could afford to).

What more charming nod to the recent, romantically remembered past than a quilt covered in demure females modestly dressed, faces hidden by the ubiquitous sunbonnet? Melcher’s books made it easy.

Also in the very early 1900s, Ladies Art Company issued patterns for Sunbonnet Sue (SBS) appliques, which began showing up in the blossoming catalog business. So enduring and profitable was the little lady and her variations that McCall’s carried a version until the 1930s. They also produced a “Sunbonnet” pattern for a stuffed doll, complete with boy companion.

Probably no one spread Sue further than Ruby Short McKim, whose syndicated column appeared in more than 900 newspapers during the 1920s and 30s. She designed mail order patterns as well, entrenching SBS firmly in the American quilter’s consciousness.

What great irony – a fictional, formless, faceless female figure helped several real-life women become successful business owners and entrepreneurs, far removed from doing only the daily chores so many Sue blocks depicted. She is also shown playing and sometimes getting into trouble – just like her human counterparts.

Still an Enigma

By whatever name (Dutch Baby, Mary Ann and Mary Lou among them), Sunbonnet Sue has simple appliqué components easily sewn: The bonnet hiding her face, a bell of a dress, unarticulated arms, a shoe. From there the variations are endless: a hat band, a sleeve cap, an apron, holding something in that one blunted hand.

Parasols, skirts blown in various ways, props surrounding Sue -- all have been done and have given rise to even more names such as Old Fashioned Girl, Calico Girl, Balloon Girl, Sunbonnet Sue Running Through the Raindrops, Old Fashioned Girl in a Swing and Colonial Lady (usually only those figures with a parasol and more elegant skirt earned this last name).

The biggest change of all came when Overall Sam appeared in 1900 – same artistic concept, different gender, soon after Sue gained wide recognition. And of course he has undergone transformation and name changes, too: Overall Bill, Straw Hat Boy, Overall Boy, Sunny Jim, Dutch Boy and Overall Andy to name a few.

Featured: Overall Sam Embroidery Design

Bear in mind that in the heyday of quilt patterns published in numerous newspapers and different catalogs and by proliferating mail order pattern companies, tweaking both the pattern and name of something easily recognizable was the bread and butter of their bottom lines.

In fact, Barbara Brackman’s Encyclopedia of Appliqué shows further development of SBS blocks into specific identities including cowboys, Native Americans, African Americans and fishermen. Now we can think of Sue as a prototype, birthing a nation.

So, once a Sue does not always mean a Sue -- an even foggier aura surrounds our shady lady.

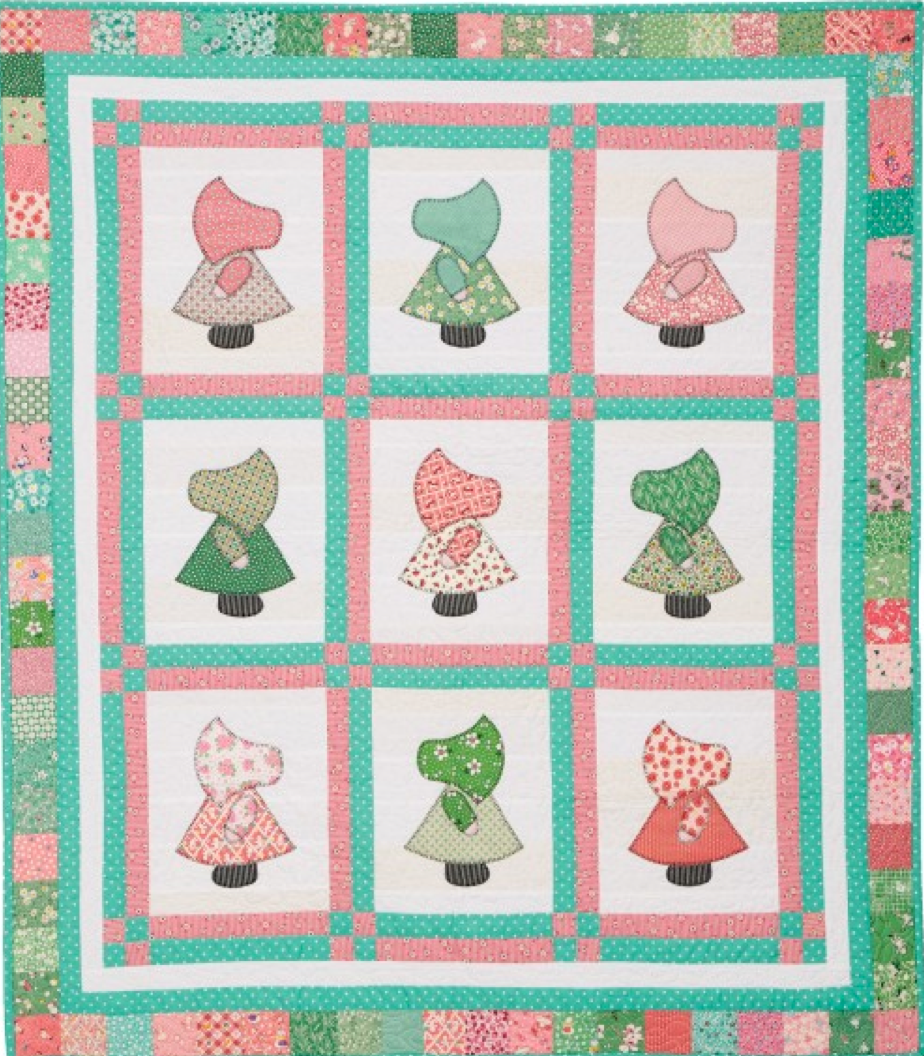

It is interesting that Sunbonnet Sues tend to show up in flocks. You don’t often see a Sunbonnet Sue working or playing solo on, say, a sampler quilt or a Log Cabin piece, chasing Flying Geese all by herself, or in the foreground of an art quilt, acting like the painter of a landscape. SBS quilts tend to look alike because even with clothing changes, most quilt makers work with one image in every block – repetition has beauty. And so many Sue quilts are sashed, which lends great regularity to the look of any multi-block quilt.

There are exceptions, of course; there always will be, especially with a pattern of widespread appeal, for quilters are inherently creative and visionary, even when they don’t think they are.

Befitting a woman of uncertain provenance, no two SBS quilts are alike. Each quilter finds Sunbonnet Sue a blank canvas for their own style and their own story and a wonderful creative outlet.

So Why Doesn’t Everyone Like Sunbonnet Sue?

Some folks say she was immortalized in song around 1906 as she was becoming famous; others say she opportunistically jumped on a literal band wagon. This cross-media exposure no doubt both increased her appeal for some and simultaneously sent many quilters – many generations of quilters – running in the opposite direction.

Either that, or they can’t fathom why anyone finds this benign (some say “spooky”) depiction of the featureless female form attractive or uplifting in any way and wouldn’t be caught dead near this appliqué pattern. Epithets about her include “insipid,” “without any discernible charm” and “over simplified to the point of being just plain dumb.”

And then there is the quilt that famously showed the many ways Sue might expire, none of them pleasant. (Her being swallowed whole by a snake – eewww!) See The Sun Sets on Sunbonnet Sue, Michigan State University, for details. Similar quilts depicting her demise have followed.

No doubt this love/hate dichotomy is what will keep Sue in our minds if not our hearts for generations to come. Her true origin, as befits a woman who engenders great passion, hardly matters.

References:

Barbara Brackman’s Encyclopedia of Applique, C & T Publishing, 2009

Moira F. Harris, Minnesota History, 2010

FREE GO! Sunny Sue Baby Quilt Pattern

After near five years as the executive book editor for the American Quilter’s Society, Andi Reynolds retired and has resumed the free lance life. She spends her time writing, quilting, cooking, and obeying the commands of her large dogs Lucky and Mousse. Her husband Dennis is the beloved co-leader of the pack. They live in Paducah, KY.

Which Fabric Cutter is Right for You?